Marine Spatial Planning

Working towards a holistic, integrated, and inclusive framework for sustainable ocean management.

Marine Spatial Planning

Working towards a holistic, integrated, and inclusive framework for sustainable ocean management

What is Marine Spatial Planning? (MSP)

MSP is defined most succinctly as a “public process of analysing and allocating the spatial and temporal distribution of human activities in marine areas to achieve ecological, economic and social objectives that have been specified through a political process” – (Ehler 2007 cited in Ehler 2021).

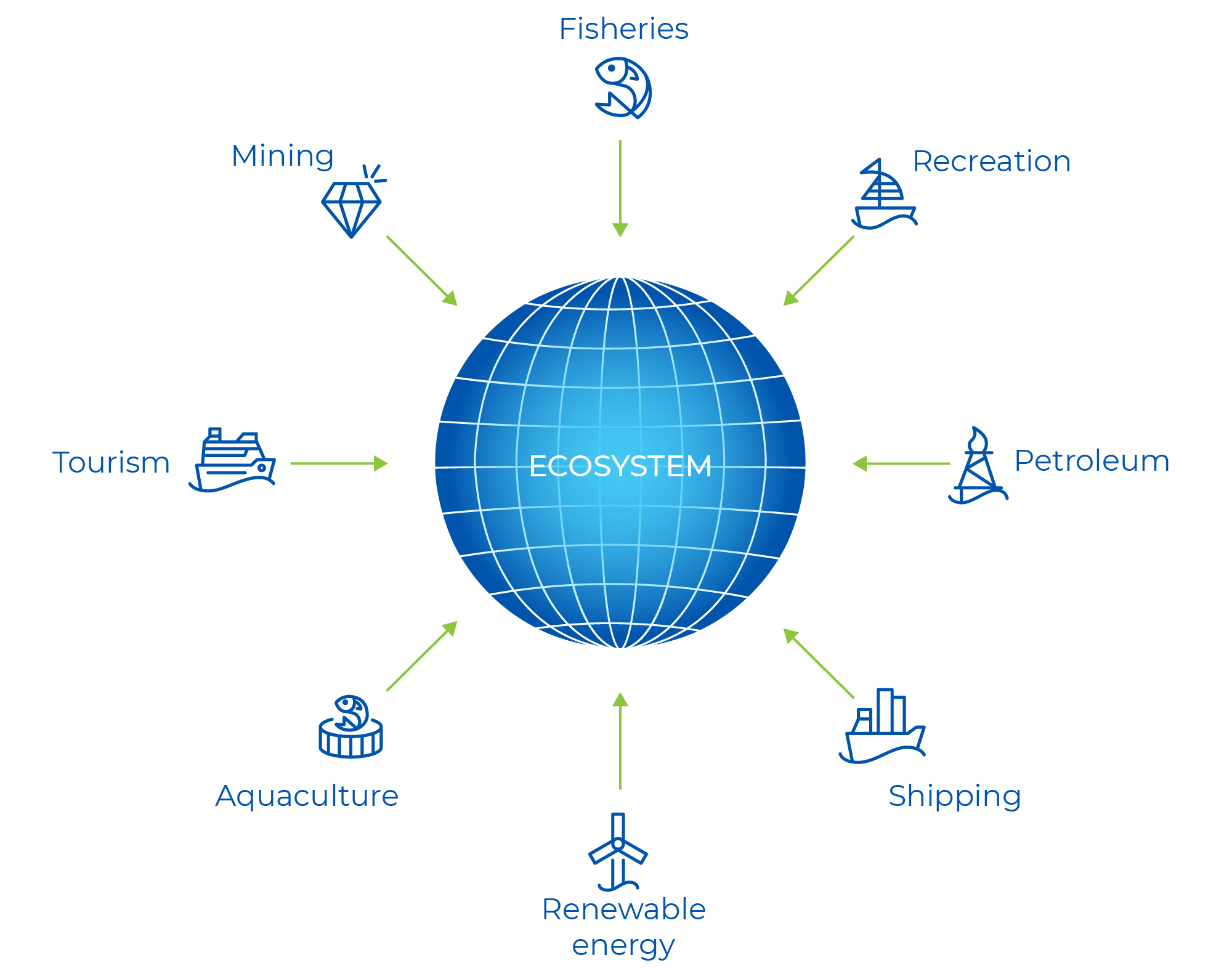

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) is a multi-objective, multi-use, integrated planning process that represents an agreed set of principles and processes to manage interactions between all uses of ocean space and their impact on the environment (Flannery and Cinneide 2012; Ehler 2021).

It has wide-reaching impacts for stakeholders by synthesizing information and threats to the marine environment, resources, ecosystem services, uses and values (Agardy et al. 2011). It is not intended to be a one-off process nor is it intended to produce a “master plan” or “blueprint”, rather it continually evolves and adapts as new issues/data emerge from monitoring and evaluation (Ehler 2021).

Marine spatial planning offers countries an operational framework to maintain the value of their marine biodiversity while at the same time allowing sustainable use of the economic potential of their oceans.

“As an operational framework, MSP is a multi-faceted approach that can simultaneously support the conservation of a nation’s marine environment, enable the realisation of its economic potential, and facilitate more integrated patterns of sea use among actors”

– McAteer et al. 2022

Marine spatial planning uses information on the natural system to support decision-making processes about the human system create sustainable pathways to meet the economic, environmental and social needs of societies.

The Blue Economy Marine Spatial Planning

Objectives

The primary goal of this project is to deliver forums, tools and approaches to assist regulators and industries to implement ecologically, economically, and socially sound planning in Australia’s marine environment when developing Australia’s Blue Economy.

It is not to develop a Marine Spatial Plan: rather to understand and test how MSP could be applied for the benefit of all Australians, including Indigenous Australians. The end users are all industries and groups of society with an interest in the marine estate and government departments that have policy, planning and/or regulatory responsibility for Australia’s marine estate.

Project

Scope

The scope of the project is Australia’s marine estate which includes both state and commonwealth waters. The end users for the project are all industries with an interest in the marine estate and government departments that have policy, planning and/or regulatory responsibility within the marine estate.

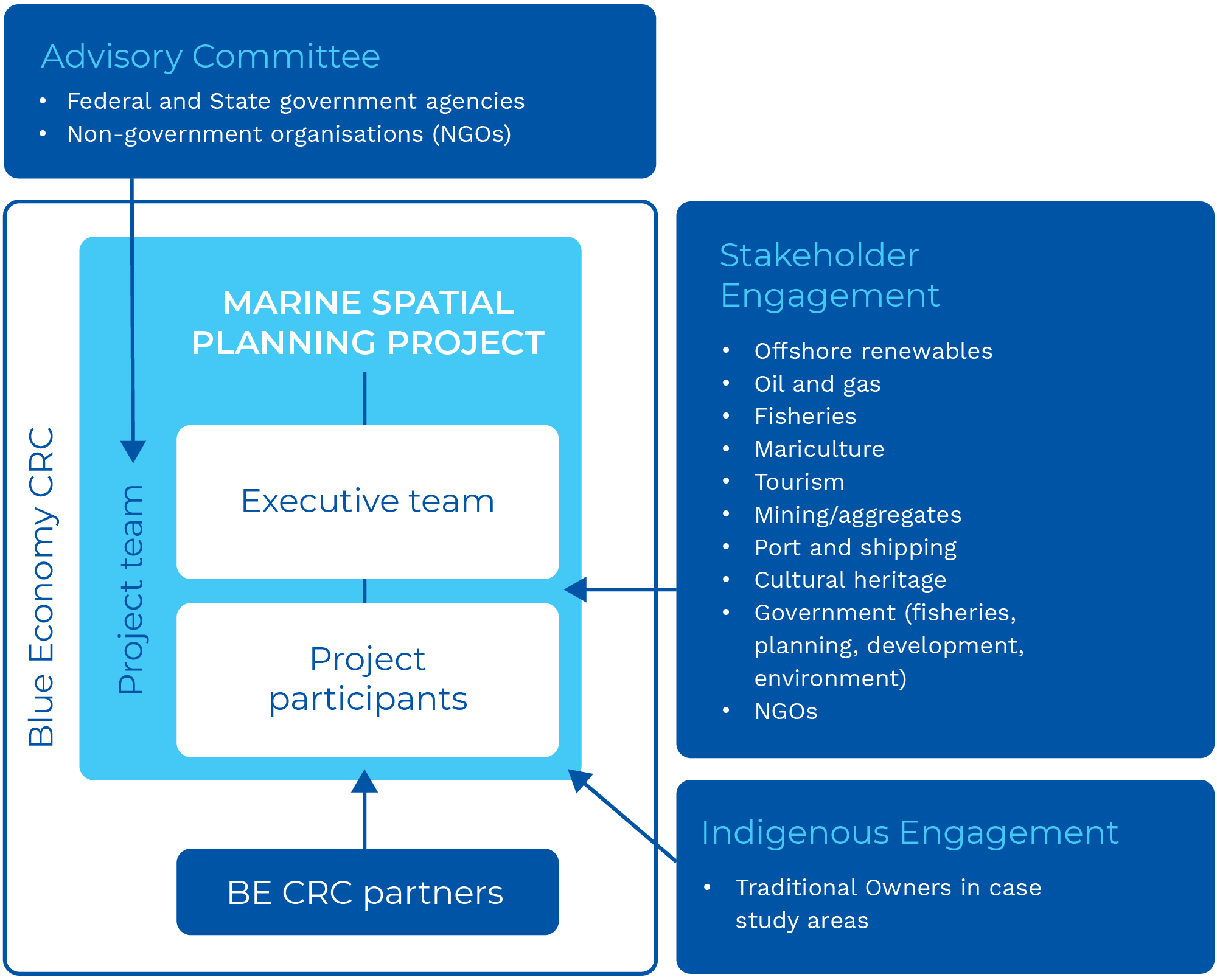

The project is guided by ongoing stakeholder engagement and interactions with the following communities:

Peak bodies, government departments and organisations with an interest in the marine estate;

Representatives from federal and state government and non-government organisations;

Indigenous engagement through a process that is appropriate for Traditional Owners.

Outputs of this project will support both industry, government and wider society with a workable pathway for more holistic and efficient system of planning activities in Australia’s marine estate.

Project

Workstreams

FRAMEWORK

Develop a national, workable framework for MSP in Australia’s marine estate that is consistent with emerging international practice and includes options that will allow regulators to meet the requirements of the legislative frameworks and operational needs.

DATA

Characterise and collate spatio-temporal data in Australia’s EEZ needed to support MSP, identify where data gaps exist and create a portal to access the data. This will be achieved through engagement with data managers to identify existing data platforms and engagement with stakeholders (government and industry) to identify data needs.

CASE STUDIES

Develop decision support tools to aid site selection and MSP at local-regional scales in pre-determined case study locations. The process will be informed through extensive stakeholder engagement at the local-regional level and will be supported by extensive spatial data.

APPLICATIONS

Evaluate the interactions among ocean users and understand the cumulative impacts from cross-sector use on environmental, social and cultural values.

Frequently Asked

Questions

GOVERNANCE

In numerous countries, MSP processes have been developed and implemented across jurisdictions through steering and advisory committees. These committees invariably contain representatives from different levels of government and are tasked with implementing marine policy. For example:

- Belgium – Federal and state (Flemish) government departments are integrated through an MSP Advisory Committee which was established in 2012 by Royal Decree to develop and manage the Belgium MSP [1].

- Canada – Under Canada’s Oceans Act, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans was tasked with advancing MSP initiatives using an integrated management approach within five separate geographical areas known as Large Ocean Management Areas (LOMAs). Each LOMA is managed by a different web of committees, forums and groups involving federal, provincial and territorial government agencies, and in some cases, First Nations authorities. Some advisory groups also include industry participants, scientific organisations, and community members. While not legally binding, participating agencies align LOMA strategies and plans with their own policies and decision-making processes [2].

Other mechanisms have also been used. Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in Australia, which covers both state and federal waters, is managed by federal and states agencies together under the ministerially approved Great Barrier Reef Intergovernmental Agreement 2009. In the United States, the State of Rhode Island used its Special Area Marine Plan (a plan which is endorsed under federal legislation), to influence planning of a wind farm development in federal waters off the Rhode Island coast. The wind farm had to be spatially downsized by the federal government to minimise impacts on fish spawning areas that repopulated fisheries within state waters [3].

[1] European MSP Platform. (2022). Maritime Spatial Planning Country Information: Belgium. Retrieved May 29, 2023, from https://maritime-spatial-planning.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/download/belgium_july_2022.pdf

[2] Fisheries and Oceans Canada. (2002). Policy and Operational Framework for Integrated Management of Estuarine, Coastal, and Marine Environments in Canada. Fisheries and Oceans Canada Oceans Directorate.

[3] Blau, J., & Green, L. (2015). Assessing the impact of a new approach to ocean management: Evidence to date from five ocean plans. Marine Policy, 56, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MARPOL.2015.02.004

Many MSP processes and plans are not enshrined in legislation but instead are developed through policy and government decision making. These MSPs are then used to inform and influence decision making under existing legislative regimes including sector-based laws. For instance, Norwegian marine plans and strategies are policy based, endorsed at the parliamentary level and then implemented through decisions made under existing sector-based legislation [1].

In the United States, MSP processes have been driven by policy-based initiatives and voluntary collaborations between various levels of government. For example, ocean planning for the US Northeast region was first initiated by the Northeast Regional Ocean Council (NROC) which was voluntarily formed in 2005 by the Governors of the New England states in response to proposals for new offshore activities. Then during the Obama administration, when regional ocean bodies were formally established to implement Obama’s National Ocean Policy (since revoked), planning work for the Northeast region continued under the direction of the Northeast Regional Planning Body, a partnership between federal, state and tribal authorities. This resulted in the development and implementation of the Northeast Ocean Plan 2016. However, in 2018 when the National Ocean Policy regime was revoked, NROC resumed responsibility for region ocean planning activities through its Ocean Planning Committee, a voluntary participation between federal, state and tribal authorities. Outputs from this committee are used to inform government decision making including federal Executive Orders.

[1] MSPglobal (2022) MSProadmap: Norway. https://www.mspglobal2030.org/msp-roadmap/msp-around-the-world/europe/norway/

MSP is typically initiated through a government led process, but a few have been instigated through universities and other research organisations.

In Israel, the Israel Institute of Technology created a roadmap that served as a shadow-plan while government led MSP processes were being formulated. This university led project was conducted with the assistance of a large group of stakeholders consisting of representatives from government ministries and bodies, non-government organisations, local authorities, and marine-related business sectors [1]. Several of the planning principles from the academic plan were incorporated into the new Israel Maritime Policy [2].

In Europe, a number of universities and other research institutes were instrumental in developing MSP methodologies and plans under EU funded projects (such as ADRIPLAN, SUPREME) to promote MSP implementation in the Mediterranean Sea. Although these methodologies and plans are not endorsed by legislation or formal policy, the developed methodologies and plans showcased how MSPs could be achieved at the regional scale and across country borders.

In South Africa, the Nelson Mandela University has been leading the Algoa Bay Marine Spatial Plan Project, a pilot project funded by the National Research Foundation Community of Practice to develop a marine spatial plan for the Algoa Bay area. It is envisioned that the outputs from this project, which will include a marine spatial plan for the Algoa Bay area, as well as methodologies and tools used in developing the plan, will guide and inform the South African government in developing its larger marine area plans under the relatively new Marine Spatial Planning Act (Act No. 16 of 2018).

[1] Rivers, N., Truter, H. J., Strand, M., Jay, S., Portman, M., Lombard, A. T., Amir, D., Boyd, A., Brown, R. L., Cawthra, H. C., Faure Beaulieu, N., Findlay, K., Gal, G., Grossmark, Y., Perschke, M. J., Pillay, T., Pyrgies, O., Ramakulukusha, M., Smit, K. P., … Vermeulen (Miltz), E. A. (2022). “Shared visions for marine spatial: Insights from Israel, South Africa, and the United Kingdom.” Ocean and Coastal Management, 220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2022.106069

[2] https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/generalpage/policy_maritime/he/Water_Energy_Communication_full_strategy_document_translated_nov22.pdf

MSP can provide a common baseline for discussion between stakeholders, rightsholders and planners, by spatially depicting environmental features (including areas of environmental importance), and existing and future user and rightsholder interests, within a planning area. This information then guides the planning process in resolving conflicts in one of two ways. Either [1]:

- by averting spatial competition – ensuring incompatible activities don’t take place in the same area, and are not located within a distance that could negatively impact other activities; or

- by mitigating the impacts of an unavoidable conflict, usually through compensatory or other measures that offset the impacts of a marine use. This may be the case where there is already an entrenched marine use within a proposed marine planning area that cannot be relocated, or spatial options are limited because a marine area is busy with a multitude of uses.

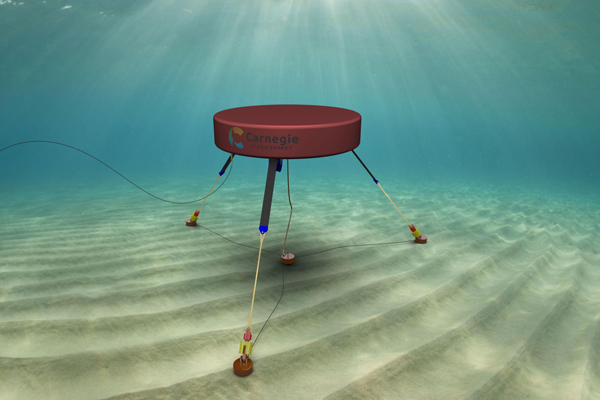

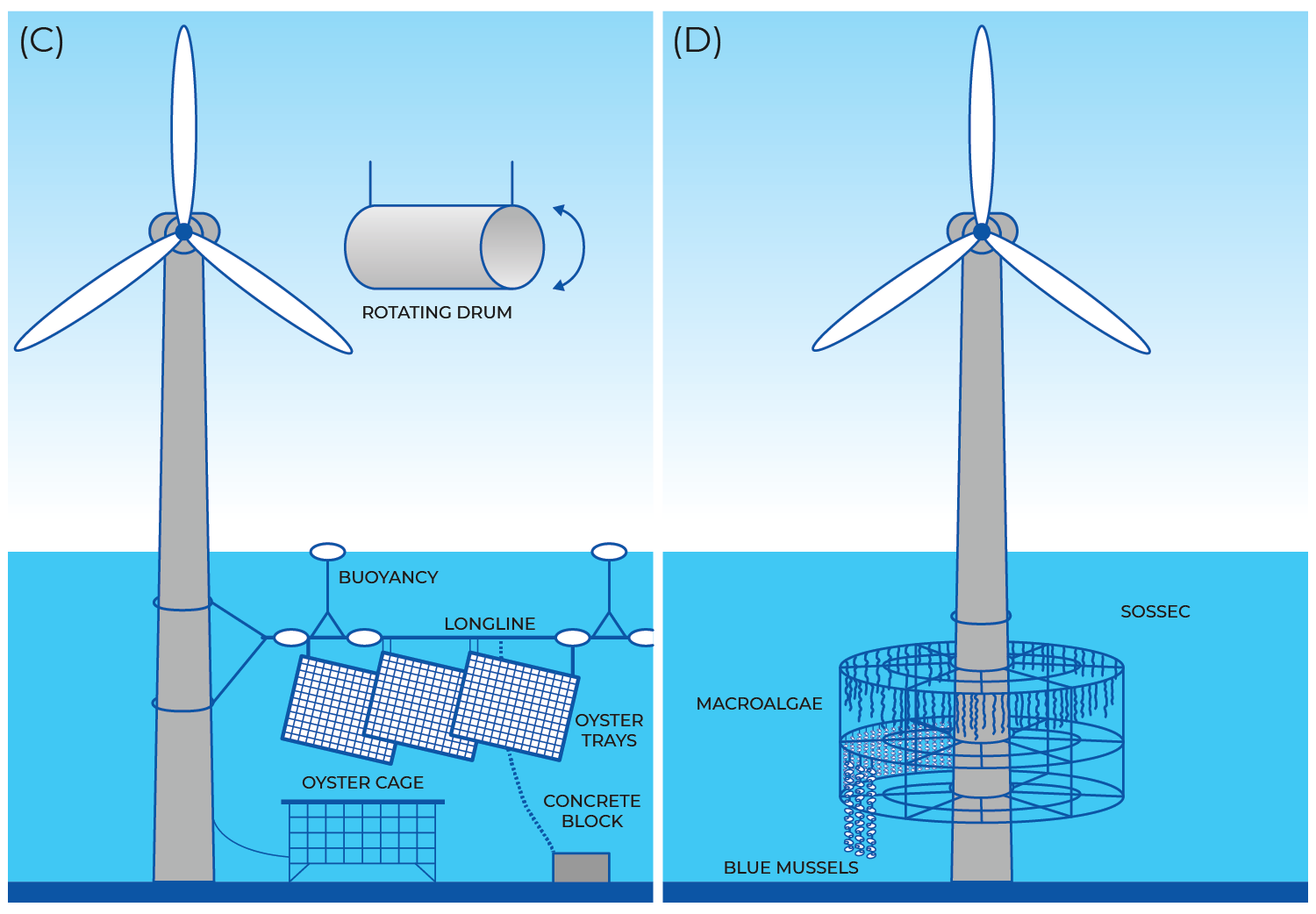

A growing approach to mitigating conflicts (or what are at first are perceived as conflicts) is multi-use planning. This involves identifying and nurturing synergies between marine uses so they can be multi-use in some way. For instance, synergies have been recognised between wind farms and tourism, and wind farms and aquaculture. In the coastal areas of Denmark, Belgium, Germany, Sweden and the United Kingdom, tourism is consciously integrated with wind farms by offering boat tours to wind farms. In Middelgrunden Offshore Wind Farm, Denmark tourists can take a climbing tour of one of the turbines. In the last ten years, numerous projects in the North Sea have also piloted wind farms co-located with aquaculture farms of seaweed, mussels, oysters and lobsters [2] (Figure 1). Co-location is a growing area of research and development which could help avoid certain sector conflicts.

Figure 1 – Examples of how aquaculture can be co-located with wind farms.

Source: Buck, B.H. et al. (2017). The German Case Study: Pioneer Projects of Aquaculture-Wind Farm Multi-Uses. In: Buck, B., Langan, R. (eds) Aquaculture Perspective of Multi-Use Sites in the Open Ocean. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51159-7_11

[1] European MSP Platform (2019) Addressing conflicting spatial demands in MSP: Considerations for MSP planners, Final Technical Study. European Commission, Brussels. https://maritime-spatial-planning.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/20190604_conflicts_study_published_0.pdf

[2] Schultz-Zehden, Angela et al. (2018). Ocean Multi-Use Action Plan, MUSES project. Edinburgh. https://www.submariner-network.eu/images/projects/MUSES/MUSES_Multi-Use_Action_Plan.pdf

STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT

Stakeholders have been engaged through membership on decision making or advisory committees, small group meetings and workshops, online materials, and public meeting and forums. In the United Kingdom, Statements of Public Participation for each proposed marine plan are required to be submitted to the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs for approval. These statements set out intended processes for engaging stakeholders and will usually contain a mixture of face to face, online and targeted communication methods[1].

Table 1 – Methods suggested by UK’s Guidance: Marine planning – statement of public participation. (Source)

| Face to face | Digital | Direct |

| Meetings | Gov.uk website | |

| Bespoke workshops | Social Media | Newsletters |

| Consultation events | Webinars | Questionnaires |

| Stakeholder events | Videos/animations | Consultations |

| Blogs | ||

| Explore Marine Plans |

In the United States, most marine planning initiatives seek to engage a range of stakeholders. This was the case with the Northeast Ocean Plan 2016, developed by the Northeast Regional Planning Body (NERPB; https://neoceanplanning.org/plan/). NERPB itself was constituted by 11 federal, 10 state and 9 tribal bodies. While federal agency participation in NERPB was mandatory, state and tribal organisation involvement was voluntary. Input from other stakeholders [2] was obtained via public comment at biannual NERPB meetings, public workshops convened prior to each NERPB meeting, and public meetings held during public comment periods. The NERPB also instigated a targeted outreach programme which included workshops with scientists, information-gathering meetings with specific stakeholder groups, and conversations with smaller groups of stakeholders. Websites and social media were used extensively throughout the MSP process as well.

In another United States example, a highly consultative approach was used to develop Rhode Island’s Ocean Special Area Management Plan (Ocean SAMP) [3]. This included establishing a stakeholder group chaired by an external facilitator, dedicated advisory committees for each topic in the plan, a science task force, a state and federal agency coordination group, a legal committee, and tribal advisors. The stakeholder group consisted of representatives from municipalities abutting the project boundary, the Narragansett Indian Tribe, fishermen’s organizations, recreation and tourism interests, environmental organizations, marine trades, commercial interests, and other groups with a broad interest in the area. Membership in the stakeholder group was targeted in order to allow each represented group adequate opportunity to offer meaningful input to the process. Over 100 formal meetings were held with 50 organisations during plan development. A dedicated website was established that provided information about the project, its activities, calendar of events and outputs [4]. Research findings and their implications were presented at monthly stakeholder meetings, and major public workshops and seminars featured experts on various Ocean SAMP issues [5]

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/marine-planning-statement-of-public-participation/marine-planning-statement-of-public-participation

[2] Commercial fishers, Recreational fishers, Aquaculture companies and users, Marine transport companies and users, scientists and researchers, Environmental and conservation organizations, Renewable energy companies, Oil, gas, and extractive resource companies, Recreational users (boaters, beach front owners, scuba dives, surfers, etc.)

[3] https://seagrant.gso.uri.edu/oceansamp/stakeholders.html

[4] https://seagrant.gso.uri.edu/oceansamp/index.html

[5] Olsen, Stephen, McCann, Jennifer & Fugate, Grover. (2014). The State of Rhode Island’s pioneering marine spatial plan. Marine Policy, 45. https://doi.org/26–38. 10.1016/j.marpol.2013.11.003

Not all MSP approaches have enabled equal representation for stakeholders (e.g., Germany, Norway). However, some MSP processes have embraced more inclusive approaches by adopting consensus-based decision making. For example, the Stakeholder Advisory Council (SAC) established to advise on Canada’s Eastern Scotian Shelf Integrated Management Initiative used this approach. It meant that all stakeholder concerns had to be addressed for a decision to be carried, no matter the number of SAC members that represented each respective stakeholder (see Table 2). However, because of the wide spectrum of interests, reaching consensus on a detailed plan proved difficult resulting in a more high-level strategic plan [1].

Table 2 – Stakeholder Advisory Council membership for the Canada’s Eastern Scotian Shelf Integrated Management Initiative. Source: Flannery, W., & Ó Cinnéide, M.. (2012). Deriving Lessons Relating to Marine Spatial Planning from Canada’s Eastern Scotian Shelf Integrated Management Initiative. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 14(1), 97–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908x.2012.662384

| Stakeholder group | Number of seats |

| Government of Canada | 4 |

| Conservation groups | 3 |

| Government of Nova Scotia | 3 |

| Community groups | 2 |

| Academic and private sector research | 2 |

| Government of Newfoundland and Labrador | 1 |

| Transportation | 1 |

| Municipal government | 2 |

| Offshore Petroleum Board | 1 |

| Telecommunications | 1 |

| Aboriginal peoples | 2 |

| Tourism | 1 |

| Fisheries | 5 |

| Citizens at large | 1– 2 |

| Oil and gas | 2 |

| Total | 31 – 32 |

[1] Flannery, W., & Ó Cinnéide, M.. (2012). Deriving Lessons Relating to Marine Spatial Planning from Canada’s Eastern Scotian Shelf Integrated Management Initiative. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 14(1), 97–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908x.2012.662384

Engagement can range from tokenistic post-planning mechanisms with little decision-making influence to full participatory involvement. In North America, First Nations representatives have been integral to marine planning through membership on decision-making committees and bodies.

In Canada, seventeen First Nations communities partnered with the British Columbia government to establish the Pacific North Coast Marine Plan Partnership (MaPP) which produced the Pacific North Coast regional plan. Planning was scaled up from First Nations territories to sub-regional to regional (Table 3). Territorial marine use plans were developed by the respective First Nations communities and focussed solely on First Nation goals and aspirations. This was achieved through a First Nation’s Community Co-ordinator working with a committee of First Nations community members including food harvesters, commercial fishers, youths, Elders and Hereditary leaders. The Community Coordinator then collaborated with aggregate First Nations organisation working at the sub-regional and regional level to harmonise and integrate territorial plans into the wider regional plan with the provincial government [1].

In the United States, during the Obama administration, the regional planning bodies that were established under the National Ocean Policy and responsible for developing regional ocean plans, including the Northeast Ocean Plan and Mid-Atlantic Regional Ocean Action Plan, were constituted by First Nations representatives as well as federal and state government agencies [2].

Table 3 – First Nations and Aggregate Organisations during territorial and MaPP planning. Source: Diggon, S., Butler, C., Heidt, A., Bones, J., Jones, R., & Outhet, C. (2021). The Marine Plan Partnership: Indigenous community-based marine spatial planning. Marine Policy, 132, 103510–103510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.04.014

| Sub-region | First Nation | Sub-regional Aggregate/Organization | Regional Aggregate Organization |

| Haida Gwaii | Old Massett Village Council

Skidegate Band Council |

Council of the Haida Nation | Coastal First Nations

– Great Bear Initiative Provided coordination, technical and secretariat functions |

| North Coast | Gitga’at Nation

Gitxaała Nation Haisla Nation Kitselas Nation Kitsumkalum Nation Metlakatla First Nation |

North Coast Skeena First

Nations Stewardship Society |

|

| Central Coast | Heiltsuk Nation

Kitasoo/Xai’Xais Nation Nuxalk Nation Wuikinuxv Nation |

Central Coast Indigenous

Resource Alliance |

|

| Northern Vancouver

Island |

Qwe’Qwa’Sot’Em Nation

Gwasala Naxwaxdax’da Nation Tlowitsis Nation Da’naxda’xw Awaetlatla Nation We Wai Kum Nation Kwiakah Nation K’´omoks Nation |

Nanwakolas Council |

In South Africa, the Nelson Mandela University has been leading a project to develop a marine spatial plan for the Algoa Bay area. As part of this project, the university engaged with traditional owners to identify and integrate indigenous knowledge into the plan. Indigenous knowledge was identified through arts-based participatory research (ultimately resulting in a photographic exhibition [3]). Coastal governance authorities were also interviewed and attended workshops to understand current challenges and workarounds in coastal and ocean management, and to discuss potential traditional knowledge integration. After a year of engagements, a one-day workshop was held with all participants to view the outputs of the art-based participatory research and determine the best approaches moving forward for integrating indigenous knowledge into the plan [4].

[1] Diggon, S., Butler, C., Heidt, A., Bones, J., Jones, R., & Outhet, C. (2021). The Marine Plan Partnership: Indigenous community-based marine spatial planning. Marine Policy, 132, 103510–103510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.04.014

[2] https://marineplanning.org/projects/north-america/us-mid-atlantic/; https://marineplanning.org/projects/north-america/us-northeast/

[3] See video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AsavQOxyLFw&t=13s

[4] Rivers, N., Strand, M., Fernandes, M., Metuge, D., Lemahieu, A., Nonyane, C. L., Benkenstein, A., & Snow, B. (2023). Pathways to integrate Indigenous and local knowledge in ocean governance processes: Lessons from the Algoa Bay Project, South Africa. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9(1084674). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.1084674

SUCCESSFUL MSP

The MSP Global International Guide on Marine / Maritime Spatial Planning consider MSPs to have the best outcomes …

“when they involve all key stakeholders and are coordinated and integrated with sectoral policies and decision-making. In all cases, the defining qualities of MSP indicate that it is a public and participatory process of analysing and allocating the spatial and temporal distribution of human activities in marine areas to achieve ecological, economic, and social objectives that have been specified through a political process” [1].

An example that reflects many of these qualities is Rhode Island’s Ocean Special Area Management Plan (Ocean SAMP), a regulatory instrument developed by the State of Rhode Island, and federally approved, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972 (16 U.S.C. § 1451). Ocean SAMP was one of the first comprehensive marine spatial plans established in the United States, and guided the siting and permitting of the nation’s first offshore wind farm [2]. The plan was developed with extensive stakeholder involvement (for more details see Stakeholder Engagement questions) resulting in widespread support for the plan. Prioritised research was undertaken and shared with stakeholders to inform plan development. This resulted in an unprecedented amount of new knowledge about the planning area’s ecosystems and human uses. Collaboration across state and federal agencies was integral to the plan’s development and has resulted in an integrated approach to managing marine uses in Rhode Island’s state and adjacent federal waters [3].

Another example is the regional marine plan developed for Canada’s Pacific North Coast [4]. This plan was completed and implemented through a co-led partnership between First Nations and the provincial government (Marine Plan Partnership (MaPP)). Local governments, sector-based organisations and community groups provided input through membership on advisory committees. Although the resulting MaPP planning instruments are not legally binding, they have remained unchallenged since their introduction (attributed to high stakeholder involvement during plan formulation), and annual surveys of government officers indicate the MaPP plans are consistently referenced in reports provided to decision makers, with decision outcomes aligning with MaPP policy [5].

[1] NESCO-IOC/European Commission. 2021. MSPglobal International Guide on Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning. Paris, UNESCO. (IOC Manuals and Guides no 89). https://www.mspglobal2030.org/msp-global/international-msp-guidance/

[2] Schumann, Sarah; Smythe, Tiffany, Andrescavage, Nicole & Fox, Christian. (2016). The Rhode Island Ocean Special Area Management Plan, 2008-2015: From inception through implementation Rhode Island Sea Grant. https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/43419

[3] Carneiro, G., Roldán, S. M., & McCann, J. (2017). Rhode Island Ocean Special Area Management Plan: Case Study Summary Report. European Commission. https://iwlearn.net/resolveuid/ad41a0f8-5b0e-4172-a579-01c6514edc66

[5] McGee, G., Byington, J., Bones, J., Cargill, S., Dickinson, M., Wozniak, K.., & Pawluk, K. A. (2022). Marine Plan Partnership for the North Pacific Coast: Engagement and communication with stakeholders and the public. Marine Policy, 142, 104613. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MARPOL.2021.104613

The reason for failure can vary. Some MSP initiatives failed to fulfil their objectives because of changes in government or policies. For example, regional integrated marine planning for Canada’s Large Ocean Management Areas, as envisaged by Canada’s Oceans Strategy[1], stalled when the national government withdraw its support and funding. This meant that the original spatially based, comprehensive, multi-scale planning initiative had to be downsized to a high level, non-spatial, strategic plan[2]. Fortunately, the planning initiative was successfully revived by the Pacific North Coast Marine Plan Partnership (see preceding question on MSP successes). In the United States, implementation of regional marine plans, under the National Ocean Policy introduced by the Obama administration, were thwarted when the Trump administration subsequently revoked the National Ocean Policy and associated regional ocean planning bodies, leaving only two of the nine regional marine areas with federally approved plans [3].

As well as ‘failures to launch’, some MSPs have been criticised for failure to adopt a more stakeholder inclusive process for marine planning, particularly in the European / UK context where a top-down approach is common (i.e., top levels of government have all the decision making power for marine planning issues) [4]. Also, where MSPs are focussed on achieving certain objectives it can fail to address conflicting stakeholder positions. For example, marine planning in the German North Sea’s exclusive economic zone has been perceived as facilitating offshore wind development at the expense of other uses, with conflicts remaining unresolved[5].

[1] Fisheries and Oceans Canada. (2002). Policy and Operational Framework for Integrated Management of Estuarine, Coastal, and Marine Environments in Canada. Fisheries and Oceans Canada Oceans Directorate.

[2] Diggon, S., Bones, J., Short, C. J., Smith, J. L., Dickinson, M., Wozniak, K., Topelko, K., & Pawluk, K. A. (2022). The Marine Plan Partnership for the North Pacific Coast – MaPP: A collaborative and co-led marine planning process in British Columbia. Marine Policy, 142, 104065. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MARPOL.2020.104065

[3] Ehler, C. N. (2021). Two decades of progress in Marine Spatial Planning. Marine Policy, 132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104134

[4] Jones, P. J. S., Lieberknecht, L. M., & Qiu, W. (2016). Marine spatial planning in reality: Introduction to case studies and discussion of findings. Marine Policy, 71, 256–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.04.026

[5] Aschenbrenner, M., & Winder, G. M. (2019). Planning for a sustainable marine future? Marine spatial planning in the German exclusive economic zone of the North Sea. Applied Geography, 110, 102050. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APGEOG.2019.102050

Successful MSP processes facilitate exchanges of information, ideas and views among a range of stakeholders. Educating stakeholders and other planning participants allows them to consider other points of view and generate new solutions to potential conflicts and problems. For example, the planning framework for Canada’s Eastern Scotian Shelf Integrated Management Initiative included a Stakeholder Advisory Council (SAC). Members of the SAC were surveyed to obtain feedback on their stakeholder experiences. One member enthused how they benefited from learning about new scientific studies and what other sectors were doing, which often reprioritised their own planning work. Another member mentioned they gained a better appreciation of how their stance might impact others and how working together might reduce those impacts[1].

[1] Flannery, W., & Ó Cinnéide, M.. (2012). Deriving Lessons Relating to Marine Spatial Planning from Canada’s Eastern Scotian Shelf Integrated Management Initiative. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 14(1), 97–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908x.2012.662384

Many MSP examples seek to guide future uses of their ocean space and account for future changes. For instance, in England:

- English waters are divided into 11 regional marine areas, each managed by a long-term marine plan of 20 years. These plans are reviewed every few years to ensure they remain effective (i.e., achieve objectives) and account for new developments, data and policies;

- spatial mapping demarcates areas for future renewable energy projects, undeveloped discoveries of oil and gas[1] and future carbon storage areas;

- each marine plan incorporates policies that require marine use proponents to address future climate change impacts. For example, an application for a proposed aquaculture project will be required to demonstrate that for the lifetime of the project: 1) they are resilient to the effects of climate change 2) they will not have a significant adverse impact upon any climate change adaptation measures[2].

Some marine planning projects have also used scenario building tools to create and consider alternative visions for a marine area’s future. For example, the Future Trends in the Celtic Seas project, completed in 2017 by the Celtic Seas Partnership, plotted the potential impact of different growth scenarios in the Celtic Seas region on a range of different marine sectors, from commercial fisheries to oil and gas production, over twenty or so years. Three growth scenarios were generated: Business as Usual, Nature @ Work (maximising ecosystem services) and Local Stewardship (local decision-making and differentiation). Future development was plotted for each of these scenarios, highlighting future opportunities and conflicts that may arise. This three-scenario process was subsequently adopted by UK’s Marine Management Organisation to develop England’s 11 regional marine plans[3].

[1] https://explore-marine-plans.marineservices.org.uk/

[2] UK Marine Management Organisation (2020) A hypothetical example of marine plan use: Decisions in accordance with the marine plan (section 58(1) of the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009). UK Marine Management Organisation, London. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/958980/200428_S58-1_Legal_Approved_V2.pdf

[3] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/futures-analysis-for-the-north-east-north-west-south-east-and-south-west-marine-plan-areas-mmo-1127

FUNDING

Government led MSPs initiatives usually rely on direct budget allocations derived from tax revenue. However, there are some initiatives that are funded from other sources including grants and philanthropic donations from international and multi-national organisations, foundation grants, and funding from collaborations with other non-government organisations [1].

A number of MSP initiatives also rely on marine user fees as revenue to support their operations. In China, a sea use fee (SUF) system established under China’s Administration of the Use of Sea Areas Law requires all marine users to pay a fee as prescribed by the State Council which takes into account the amount of revenues received from the marine use as well as the damage the use may cause to the natural environment[2]. Some of these fees are a one-off charge while others are paid annually. Between 2002 to 2015, approximately RMB 75.89 billion (about US$11.02 billion) in SUFs were charged. Another example is the Great Barrer Reef Marine Park (GBRMP), which imposes an “environmental management charge” on most commercial activities including tourist activities (e.g., all visitors to the GBRMP pay a daily fee). These fees are then directly applied to managing the marine park[3]. In the 2018-19 financial year (prior to COVID-19 impacts), nearly AUD$11.5 million in environmental management charges were collected representing 14% of the GBRMP Authority’s annual revenue[4].

[1] https://www.mspglobal2030.org/resources/key-msp-references/step-by-step-approach/obtaining-financial-support/

[2] Qi Yue, Meng Zhao & Jing Yu (2018) Sea Use Fees in China: An Effective Economic Tool for Sea Use Management, Coastal Management, 46:5, 510-526. https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2018.1498715

[3] https://www2.gbrmpa.gov.au/access/environmental-management-charge

[4] Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2019) Annual report 2018-2019. GBRMPA, Townsville. https://elibrary.gbrmpa.gov.au/jspui/handle/11017/3527

There are a number of examples where monetary compensation has been used. In the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park when ‘no-take’ zones were increased in 2004 from 4 – 33%, the federal government introduced a structural adjustment package to compensate commercial fishers for loss of revenue. The initial budget was AUD$10.2 million but it blew out to ~$250 million due to rent seeking and political manipulation (Macintosh et al., 2016). In the United States, compensation packages have been used as a tool to resolve conflicts between fishers and wind farm proposals. Presently, Revolution Wind is negotiating terms with Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Management Council to proceed with an offshore wind farm project. Current terms propose a payment of $12 million to directly compensate commercial and charter fishing industries plus additional payments to fund research, community initiatives and navigational equipment[1].

Other types of compensation may also be used to resolve conflicts. In 2021, the UK Department of Environment Food and Rural Affairs issued a draft best practice paper to guide the government in dealing with conflicts between placement of marine developments and marine protected areas. Compensation measures were explained using a wind farm development where seabirds could be impacted by ‘birdstrike’. The paper suggested a number of non-monetary measures, including the developer implementing controls on bird predation at nearby seabird nesting sites, and establishing a new nesting site area away from the wind farm[2].

[1] https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/4-hours-not-enough-for-vote-on-revolution-wind-proposal-in-r-i/ar-AA1ahCA9

[2] UK Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs. (2021). Best practice guidance for developing compensatory measures in relation to Marine Protected Areas (For consultation). https://consult.defra.gov.uk/marine-planning-licensing-team/mpa-compensation-guidance-consultation/supporting_documents/mpacompensatorymeasuresbestpracticeguidance.pdf

GENERAL

MSP has been defined as “a public process of analysing and allocating the spatial and temporal distribution of human activities in marine areas to achieve ecological, economic and social objectives that have been through a political process.”[1]. It is not one specific tool but a multi-objective, mulit-use, integrated planning process that continuously evolves and adapts over time as new data becomes available from monitoring and evaluation. MPAs, on the other hand, are a spatial allocation tool aimed at protecting marine species and habitats through zoning. MPAs are one of many tools commonly incorporated into MSPs.

[1] Ehler, C. N., & Douvere, F. (2010). An International Perspective on Marine Spatial Planning Initiatives. In Environments Journal (Vol. 37, Issue 3).

Plans are scaled at either a local, state, regional or national level. The scale of plans in many cases is limited by the jurisdictional limits of the agencies seeking to create the MSP. However, the scale may also by defined by other pre-existing political/administrative delineations, size of ecosystems (where an ecosystem-based approach is adopted), physical attributes of the marine area, coastal population distributions, ocean uses and human impacts.

For example:

- Baltic Sea – this semi-enclosed sea is bordered by nine EU member states. While the basin’s physical attributes lend themselves to developing a basin-wide MSP, separate MSPs were developed by each member State limited to their territorial waters as defined by international law. However, EU legislation and policy is now driving cross-border initiatives to integrate these separate country plans[1].

- England – marine planning is based on 11 regional marine areas. These areas were established in consultation with stakeholders after considering a myriad of factors including bio-geographical features, terrestrial local authority and regional planning boundaries, river basin district delineations, fishing districts, designated conservation areas, distribution of coastal populations and costs in administering each separate plan[2].

- United States – regional marine areas were defined primarily based on large marine ecosystems (LMEs), but with modifications to, include the entire U.S. exclusive economic zone and its continental shelf, and to align with existing state borders and pre-existing regional ocean governance activities[3].

[1] European MSP Platform. (2022). Baltic Sea | The European Maritime Spatial Planning Platform. Retrieved April 27, 2023, from https://maritime-spatial-planning.ec.europa.eu/sea-basins/baltic-sea-0

[2] Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs. (2009). Consultation on marine plan areas within the English Inshore and English Offshore Marine Regions. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20101109165532/http://www.defra.gov.uk/corporate/consult/marine-plan/index.htm

[3] Interagency Ocean Policy Task Force. (2010). Final Recommendations of the Interagency Ocean Policy Task Force July 19 2010. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/files/documents/OPTF_FinalRecs.pdf

MSP is intended to overcome inefficiencies that exist in fragmented governance, including inter-agency conflicts, multi-agency responsibilities and prolonged licencing procedures (Flannery et al., 2016). Many MSPs with a blue economy focus have taken steps to streamline their government approval processes and map out suitable areas for wind and aquaculture development.

In Belgium, prior to their MSP, offshore wind farms were opposed by local communities, with one project allegedly derailed due to community objections on the basis of blocking coastal views. This led to increased development costs every time an application failed or imposed further conditions, including costs for environmental assessments, site surveys and piloting, as well as delay costs (Blau & Green, 2015). Since the introduction of Belgium’s Master Plan declared an area dedicated to wind energy projects, development has escalated and are now approved on a competitive tender basis (https://economie.fgov.be/en/themes/energy/belgian-offshore-wind-energy).

A number of mechanisms can be used to manage uncertainty in MSP decision-making when data is lacking:

- Precautionary principle – This key scientific principle is integral to most MSP initiatives. In the context of MSP, it means that if an action might cause severe or irreversible harm to society or the environment, lack of proof of that harm is not sufficient to allow the action to proceed. The burden of proof that no harm will occur falls on those who advocate taking the action.

- Modelling – Many areas of marine management are plagued by data gaps and uncertainties, from fisheries management to climate change planning. When hard data is lacking, it is common for organisations to use mathematical modelling to analyse cause/effect, and make predictions for a range of scenarios in order to address uncertainties[1].

- Adaptive management – The MSP process is cyclical[2]. Each cycle of MSP ends with an evaluation of the plan’s performance against its objectives. The outputs of this evaluation, together with any new developments and scientific data, feeds into the next cycle of planning. This ensures that if planning decisions prove to be sub-optimal (due to lack of data at the time or otherwise), they can be addressed during the next planning cycle.

[1] Heymans, J. J., Bundy, A., Christensen, V., Coll, M., de Mutsert, K., Fulton, E. A., Piroddi, C., Shin, Y. J., Steenbeek, J., & Travers-Trolet, M. (2020). The Ocean Decade: A True Ecosystem Modeling Challenge. Frontiers in Marine Science, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.554573

[2] Ehler, C. (2014). A Guide to Evaluating Marine Spatial Plans. UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, Paris. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000227779

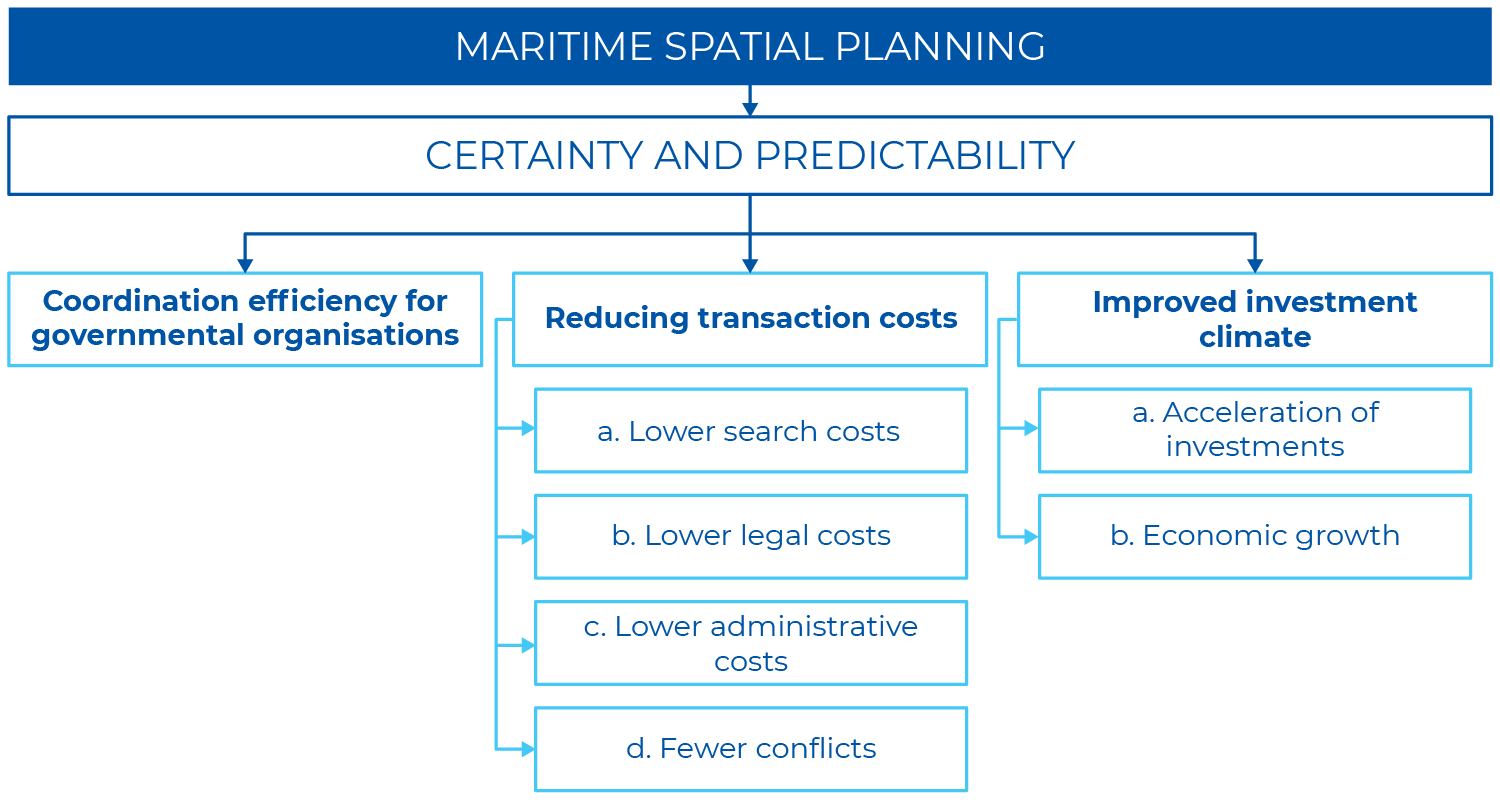

In 2011, the European Union’s Maritime Affairs and Fisheries office released a report on the economic effects of MSP, listing a range of economic benefits[1]. These benefits included:

- cost savings through integrating and aligning government processes (e.g., one-stop shop for approvals) thereby removing redundancy in government processes. These savings would arise from lower administration, employment and overhead costs per procedure;

- reducing transactions costs including search, legal, administrative and conflict resolution costs;

- accelerating investment and economic growth.

(see Figure 2)

Figure 2 – Direct economic benefits from the certainty and predictability of MSP. Source: European Union Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (2011) Study on the economic effects of Maritime Spatial Planning Final report. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

However, quantifying the exact economic benefits of MSP remains elusive due to difficulties in isolating the effects of MSP from other factors (e.g., commodity prices, Brexit, COVID-19), poor data availability and difficulties in valuing in-tangible benefits[2]. However, a recent study that proposed a method for estimating economic benefits using Belgium, Germany and Norway as case studies, found production values were boosted for most sectors with the advent of MSP[3].

[1] European Union Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (2011) Study on the economic effects of Maritime Spatial Planning Final report. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. https://maritime-spatial-planning.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/economic_effects_maritime_spatial_planning_en1.pdf

[2] COGEA, CETMAR, Poseidon, Seascape Belgium, Universidade de Vigo (2020) Study on the economic effects of Maritime Spatial Planning: Final report Abridged Version. European Commission, Brussels. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/254a6ac4-b689-11ea-bb7a-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

[3] Surís-Regueiro, J. C., Santiago, J. L., González-Martínez, X. M., & Garza-Gil, M. D. (2021). An applied framework to estimate the direct economic impact of Marine Spatial Planning. Marine Policy, 127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104443

REFERENCES

Agardy T, Notarbartolo di Sciara G, Christie P (2011) Mind the gap: Addressing the shortcomings of marine protected areas through large scale marine spatial planning. Marine Policy 35, 226-232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2010.10.006

McAteer B, Fullbrook L, Liu W-H, Reed J, Rivers N, Vaidianu N, Westholm A, Toonen H, van Tatenhove J, Clarke J, Ansong JO, Trouillet B, Frazão Santos C, Eger S, ten Brink T, Waden E, Flannery W (2022) Marine Spatial Planning in Regional Ocean Areas: Trends and Lessons Learned. Ocean Yearbook 36, 346–380. http://doi.org/10.1163/22116001-03601013

Ehler C (2021) Two decades of progress in Marine Spatial Planning. Marine Policy 132, 104134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104134

Flannery W, O’Cinneide M (2012) Deriving lessons Relating to Marine Spatial Planning from Canada’s Eastern Scotian Shelf Integrated Management Initiative. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 14, 97-117. http://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2012.662384

Winther J-G, Dai M, Rist T, Hoel AH, Li Y,Trice A, Morrissey K, Juinio-Meñez MA, Fernandes L, Unger S, Fabio Scarano R, Halpin P, Whitehouse S (2020) Integrated ocean management for a sustainable ocean economy. Ecology and Evolution 4:1451-1458. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1259-6